For a couple months, I have been planning to write about the Princeton offense. It seemed to be a necessity, as it’s what Coach Brennan runs. It has obviously influenced a few of his hiring decisions over the years. Covering American University’s men’s basketball team this year would seem foolhardy without a basic understanding of this offense.

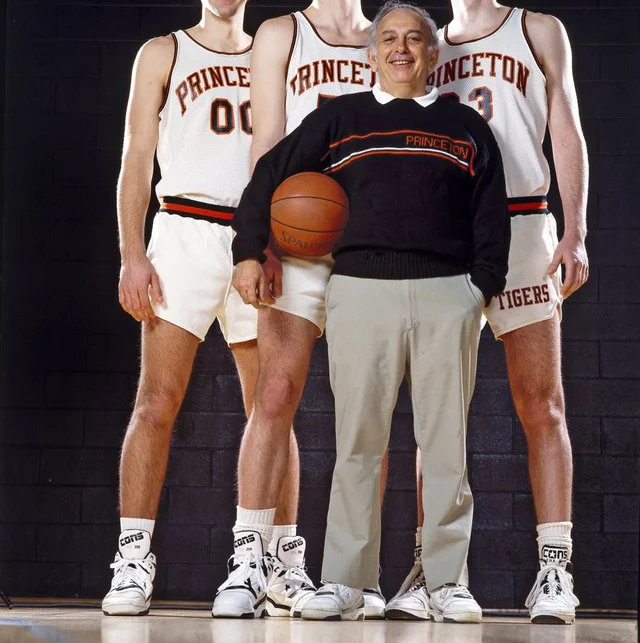

Before getting into the meat of the matter, however, I can’t write about the Princeton offense without addressing the loss the basketball community experienced early last week. Coach Pete Carril made great strides developing and popularizing the Princeton offense. His Princeton squad notably almost knocked off #1 seed Georgetown as a 16-seed in the 1989 NCAA Tournament. They defeated the defending champ UCLA as a 13-seed in 1996.

Countless tributes have been written, and rather than try to add my own words to the chorus, I want to highlight John Feinstein’s WashPo column, Nick Lorenson’s post on Mid-Major Madness, and Princeton’s own post on his passing. All of those are worth a read, especially if you hadn’t heard of Coach Carril before last week. Finally, here are Coach Brennan’s own words:

Now to transition to what the Princeton offense actually is. First, let’s get this out of the way: I don’t have a basketball background. I’m not particularly knowledgeable about various offenses and sets. I played rec basketball through middle school and have watched college and pro basketball for years, but that’s it. I’m going to explain this offense as best I can, but I might fall short in effectively conveying everything. As I learn more and discover my mistakes, I’ll post about it. And I’m always open to input, so if you happen to know better or catch an error, please let me know.

The Basics

To start, this is a complicated offense. It’s predicated on players recognizing what their defender is trying to take away and exploiting that. Plays aren’t necessarily run “for” players. Instead, the team executes a number of various series that provide scoring options. The option you take depends on how the defense is playing.

Developed in the 70s, the Princeton offense was ahead of its time in a lot of ways. First, it emphasizes a “positionless” approach to basketball, with guards and forwards needing to be able to play effectively in the backcourt, wing, and post. This is echoed today in the value of stretch fours and stretch fives, allowing a team to play five out, or in the importance placed on wings and forwards being able to defend all five positions.

It relies on scoring mainly with either a hard cut to the basket for a layup or a three-pointer. Advanced statistics have shown in recent years what is pretty intuitive: those are the most efficient shots in basketball. Years after players like Rip Hamilton made a living off of mid-range jumpers, coaches widely discourage (or at least de-emphasize) that very shot.

Now, there are drawbacks to this offense as well. It requires a lot of patience – sometimes, a team needs to run as many as four different sets in a single possession before a good shot becomes available. This results in fewer possessions over the course of the game, which increases variability. If you have a talent or athletic advantage, variability is your enemy. Therefore, this offense is best utilized by programs that might not come out on top in a typical “roll the ball out” game.

Its slow pace also makes comebacks difficult. There’s no real mechanism for getting a quick shot up. This offense uses multiple cuts, passes, and screens to produce a good look, not ideal if gametime is dwindling.

Keys to Running the Princeton Offense

In the Princeton offense, the post player is the center of the action. As such, they need to have plus awareness, exceptional passing skills, and the ability to shoot from outside. The other four players also need to be good shooters, as well as smart cutters with great timing who can quickly read a defense.

This method really only works with selfless players. The team needs to be open for whatever scoring opportunity presents itself, and needs to recognize when an option just isn’t there. Any player looking to “get theirs” might force a situation that leads to a turnover or bad shot, when running the offense would have eventually resulted in a better look. There is always something “next” in this offense, so as long as everyone does their job, there’s no bogging down.

The Princeton offense will typically start in a 2-2-1 look, with two guards in the backcourt, two forwards usually on the wing, and the 5 operating in either the low or the high post. Most sets call for a lot of cutting and clearing, most often to the corner. When on the perimeter, if you aren’t cutting, you need to be aware of open positions and looking to fill. If you’re in the corner and the wing is open, you’re often cutting to the wing. Keeping the offensive players at the free throw line or higher makes space for backdoor cuts to the hoop, resulting in the easy scoring opportunities this offense thrives on.

Conclusion

So, to recap:

- The Princeton offense is complicated. The team runs one or more sets or series until a high-percentage shot is available.

- Emphasizes a “positionless” style of play.

- It requires patience, often using a lot of shot clock and resulting in low-possession games.

- Requires selfless players who do their job and follow the system to work well.

As I mentioned, this is a complicated offense. One post really can’t do it justice. Now that I have given an overview, I will spend future posts breaking down the three main series within the offense: chin, low-post, and point.